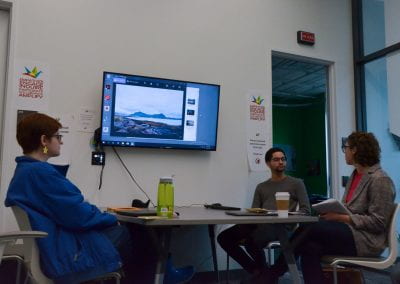

Artist-In-Residence: Taylor Freesolo Rees

Presented by the Global Lab

The Global Lab invited Taylor Rees to WPI to share her experience as a film director, photojournalist and online journalist through social media. During the 10th to the 12th of February 2020, Taylor gave various workshops and talks with the WPI community as part of the Global Lab’s StoryWorld: Artist-in-Residence Series, which is sponsored by the Women’s Impact Network. Taylor has a passion for bridging environmental and humanitarian issues and sharing the stories of people who are directly affected by climate change and resource conflicts.

Taylor’s professional journey started in Greenland when she studied climate change ecology. During her time there she developed a curiosity about the impacts that the scientists have on the local Inuit communities. “What would it feel like to have hundreds of scientists from around the world come to your hometown every summer?” Taylor stated. She moved towards telling the story with her camera, and that focused her career as a filmmaker. She then went on to build on these interests when she pursued a Master’s degree in Environmental Anthropology from the Yale School of Forestry.

In her public talk, Taylor discussed how risk narratives affect community dynamics. She shared an experience of a project in Alaska, where she encountered risk narratives around such issues as deforestation, commercial fisheries versus local fisheries access permits, and climate change. She spent two summers there and found a duality around these risk narratives, where they sometimes produce helpful outcomes such as starting positive movements, producing alliances, or bringing enemies/communities together. These narratives can also bring unintended consequences by pushing people out of the conversation movement when they feel that these narratives do not represent them.

As Taylor’s graduate course ended, she yearned for the opportunity to be a part of a movement that focuses on complex natural resource issues as they relate to engineering, science, climate science, water and food. She focused on rewriting the script as she learned about the experiences of marginalized communities that don’t fall into prevailing narratives, balancing the positives and negatives of these narratives to come up with direct solutions that allow a diversity of actors to feel ownership of the issues and potential outcomes.

Taylor dedicated herself to film making and got an opportunity to embark on a film project with her now husband, Renan Ozturk. They participated in a National Geographic assignment to define the highest peak in South East Asia since satellite technology was not able to deduce peak variances accurately. “The only way to do it is to stand on top the peaks with a high-powered GPS” she stated. The journey to the peaks started at the base of the mountain that was 150 miles from the nearest town through thick jungle. They walked on an old trade route that connected 19 villages at the base of the Himalayan range. Taylor noticed two weeks before they arrived at their destination that the story of their journey, as it had been defined by the production team, was mostly focused on themselves. She remembered the community based research experiences she had and “everything came flooding back”. She created knowledge exchange sessions with the villages that were willing, allowing the villagers to ask questions about the mission of the National Geographic team and to share the challenges the village is going through.

The National Geographic team was able to get insight into the village’s relationship with the Burmese-Myanmar government and how the state was using complicated contracts in Burmese, not the village’s native language, to control the village, as it was a world heritage site. Ultimately, the film was produced as a hiking documentary and an article was published in the National Geographic that focused on the scientific journey, not taking into consideration the complex social dynamics the team discovered in the village. When the trip ended, Taylor reflected on this experience and committed to herself that she was not going to engage in film if it was not done in a collaborative way with the communities with which she engaged. The commitment of this method of collaborative storytelling is to help the many players in positions of power like institutions, large organizations, academics, mass media and state governments to recognize the impact that projects have on diverse communities.

Taylor moved into another film project that involved the First Nations Development Institute which comprises all the Native American tribes in the United States. In the production of this film they moved around Native American Reservations and communities helping to share stories of how these communities were resisting western food systems and doing the work to grow and cultivate indigenous foods. As they moved through these different environments, they focused on understanding and incorporating the different sensitivities that are part of each community, understanding the diversities of eachg tribe with which they interacted. The communities emphasized the ethical use of social media to encourage a positive portrayal of Native Americans. Taylor’s team wrote a grant that allowed them to hire and pay writers, journalists and photographers from every tribe and community they encountered to work with them as they moved through the story. This opened a discussion floor that directly connected her with the community, allowing them to define their context and diversities, understanding the risk narratives as they related to each community.

Currently, Taylor is working on a new film in Chile telling the story of how lithium mining is affecting the livelihood of the Chilean people. She found this project at a time when she was focused on decreasing her own carbon emissions “to help the environment” and hed decided to buy an electric car. Taylor asked herself, “how are these cars being built” and she connected with a group of doctoral students, hydrologists and ecologist working with Scripps Institute of Oceanography at UCSD that is currently doing research in Chile and Argentina on decolonial feminist and community-based science. The team involves communities in the scientific research they are conducting on hydrology and contamination. These scientists have been continuously working with these communities that are being affected by lithium mining.

“Lithium mining is ground water mining; they are basically draining the water table underneath some of the most ancient indigenous territory on the planet” Taylor stated. This process is removing the none replenishable water from these ancient aquifers. The companies evaporate the water and collect lithium from the lithium rich aquifer. She is working with the researchers to tell a story of the impacts of lithium mining and the team’s approach to community-based science, and they are doing the storytelling in such a way that centers the community researchers. Taylor is working with an environmental leader in the community to produce this story and they are including the community’s ideas of their cosmological relationship between humans and the planet, reflecting the community’s understanding that humans are “going through a great turning and in our vision, its going to be okay and it’s going to happen in these ways and we want that in the film”.